This week’s Linky is all about learning in complex systems, and what gets in the way. Because we keep reaching for quick fixes (mindset shifts, root causes, other companies’ playbooks) and hoping for the best.

The question I’m thinking about is: what would change if we designed our ways of working to make learning easy and safe?

🎧 Want to listen in your favourite podcast player?

Open this post in a browser, then just below the podcast banner image, click the ‘Listen via…’ option. That will pop up a menu where you can:

Pick your preferred player

or copy and paste the RSS feed URL

📝 While you’re there, you’ll also find the transcription option. And if you listen in the Substack app, you can turn on inline subtitles as it plays.

Latest post from the Quality Engineering Newsletter

Continuing on from my Scale of Failure post, this week’s newsletter looks at how we can create more intentional failures so we can learn from them.

Spikes, proofs of concept (POCs), prototypes, and minimum viable products (MVPs) are great learning tools, but they are even better when used deliberately to reduce uncertainty.

The problem is that the intent often gets lost in teams because we use terms inconsistently, creating confusion about outcomes and expectations.

If your team uses these interchangeably, this should help you align on what each one is for, what learning it gives you, and what kind of failure it makes cheap.

New QE podcast to follow

I have not listened to this yet, but it looks like it’s worth a follow.

Episode 12 features Lisa Crispin discussing holistic testing. Via Engineering Quality Podcast | 12: Holistic Testing with Lisa Crispin | YouTube

Comparison

Compete externally and you compare.

Compete internally and you improve.

This reminded me of engineering teams. By focusing on your ways of working and how your team performs, you’re competing internally. If you focus too much on what other teams are doing, you end up competing externally.

That is not to say we should not look - other teams might have good ideas you can adapt to your context. But the focus should be: how are we getting better than yesterday? Via 3-2-1: On the ultimate form of preparation, how to increase your power, and living with conviction | James Clear

Who is accountable for quality?

Where should the accountability sit for creating decision‑ready, cross‑team insight?

This got me thinking about quality in our products, and who is accountable for it.

Ultimately, it is the CEO (or whoever is equivalent in your organisation). But that responsibility gets passed down the chain, and as it spreads through layers, it can dilute. When responsibility is shared everywhere, it often gets exercised nowhere - quality is everyone's responsibility, right?

So, where does accountability for quality land in practice? Often, with the person who has “quality” in their title.

The problem with mindsets

Here’s the real issue with mindset thining:

It assumes life works like a vending machine. Put in the right thought, get the right result.

But that’s not how complex systems work. Dave (Snowden) calls them “dispositional, not causal.” Meaning you can’t just say “if I think this, then that will happen.” Too many other things are at play.

Someone in a toxic workplace can’t just “positive think” their way to happiness. Someone struggling financially can’t just “abundance mindset” their way to wealth. The stuff around them matters way more than we admit.

That’s hard to argue with, and I’m a fan of saying mindset 🫣. So what does change behaviour? Focusing on constraints and the environment. Which is what we’re advocating for with quality engineering. Shifting the system of work to make the quality outcomes we want to occur more often than not. I’ll still talk about mindsets, but I’ll always back them up with practical behaviours that demonstrate them too. Via Dave Snowden on Changing Systems, Not Minds | Rohit Gautam | LinkedIn

Quality is a lagging indicator

Quality is a lagging indicator. Empathy is a leading one.

If you want better quality, stop asking “how do we build this?”

Start asking: “What problem is this person, in this moment, trying to solve - and what’s getting in the way?

I like this a lot. Quality is often a lagging indicator of how well we understand the people we are building for. Empathy can be a leading indicator, but only if it turns into decisions and trade-offs.

This is why the best way to understand quality is to talk to stakeholders, take time to understand what they care about, and start with the problem your solution solves for them. Via Quality is a lagging indicator. Empathy is a leading one. | Robert Meaney | LinkedIn

Build your networks

The industry loves talking about automation frameworks and CI/CD pipelines and shift-left whatever. Nobody talks about what it feels like to not have a single person to say. “Hey does this make sense to you?”

That’s the hard part. Not the technical stuff. Just, not having anyone to think with.

I noticed this early in my Principal role and had to intentionally build support networks. Not just “networking” as a career move, but having people you can think with across different contexts and disciplines. It is often mutually beneficial. Sometimes they get more than I do, and other times I get more than them. Either way, peer mentoring is valuable both in and out of your organisation. Via Hey does this make sense to you? | Christine Pinto | LinkedIn

The Spotify model didn’t work for… Spotify

And most importantly, it didn’t even work at Spotify!

Teams (sorry, “squads”!) were provided with a great deal of autonomy, but without the prerequisite foundation in practices and skills, so they were left to fend for themselves [...]

There was no agreed or common process for cross-team collaboration [...] That resulted in very high inter-team friction and overhead.

There was no single owner of engineering for the squads [...]

Spotify iterated on, and moved away from this model. We should too.

You cannot simply copy another org's practice and expect the same results. You need to understand your context and evolve from where you are. Trying to drop in someone else’s playbook rarely survives contact with your organisation’s reality, because the constraints are different. Via Spotify's Agile Transformation Lessons | Tom Geraghty | LinkedIn

Why would a delivery driver do this?

As quickly as you can think of a reason, why did the driver do this before you read on?

These are two boxes of paint:

From the post:

So what happened? The fascinating part is we’ll never really know, but here are some possibilities:

Was it capacity under load? Perhaps the driver was 40 deliveries deep into a 60-parcel route, information bandwidth maxed out, running on autopilot because the cognitive overhead of the day had exceeded what was left in the tank.

Was it domain displacement? Maybe someone who normally operates in Complex or Chaotic domains—an engineer, a strategist—now working in logistics because life shifted. Bored. Not engaged. Operating below their structural ceiling and finding small acts of mischief to create novelty.

Was it systemic friction? A person who’s been mistreated by their employer, carrying resentment, expressing micro-rebellion through small acts that won’t get them fired but send a signal. Not about my paint. About everything else.

Was it life complexity bleeding through? Social load overwhelming work capacity. A relationship ending. Financial worry. A sick parent. The person showed up physically, but their system was elsewhere.

Or was it simply exit-mode? Already resigned mentally, just running out the clock, care evaporated because the relationship with the work has already ended even if the contract hasn’t.

Which one did you go with? I defaulted to capacity under load, partly based on the drivers I have had deliver things to me. What I liked about this post is how quickly it expands the range of plausible explanations, even for something that appears to be a straightforward failure.

Now think about software engineering, which often sits in the complex domain.

If there can be this many plausible explanations for a visible “simple” failure, how many might there be for a failure in a complex system?

This is why understanding how quality is created, maintained, and lost in complex systems matters. It limits us from defaulting to a single neat story and invites us to explore the system conditions that produced the outcome.

It is also another reason psychological safety matters. Without it, you rarely learn the true reasons things fail. You learn the reasons people feel safe to say. Via Clear Domain Dysfunction: Human Capacity vs Systemic Fractures | David Howell | LinkedIn

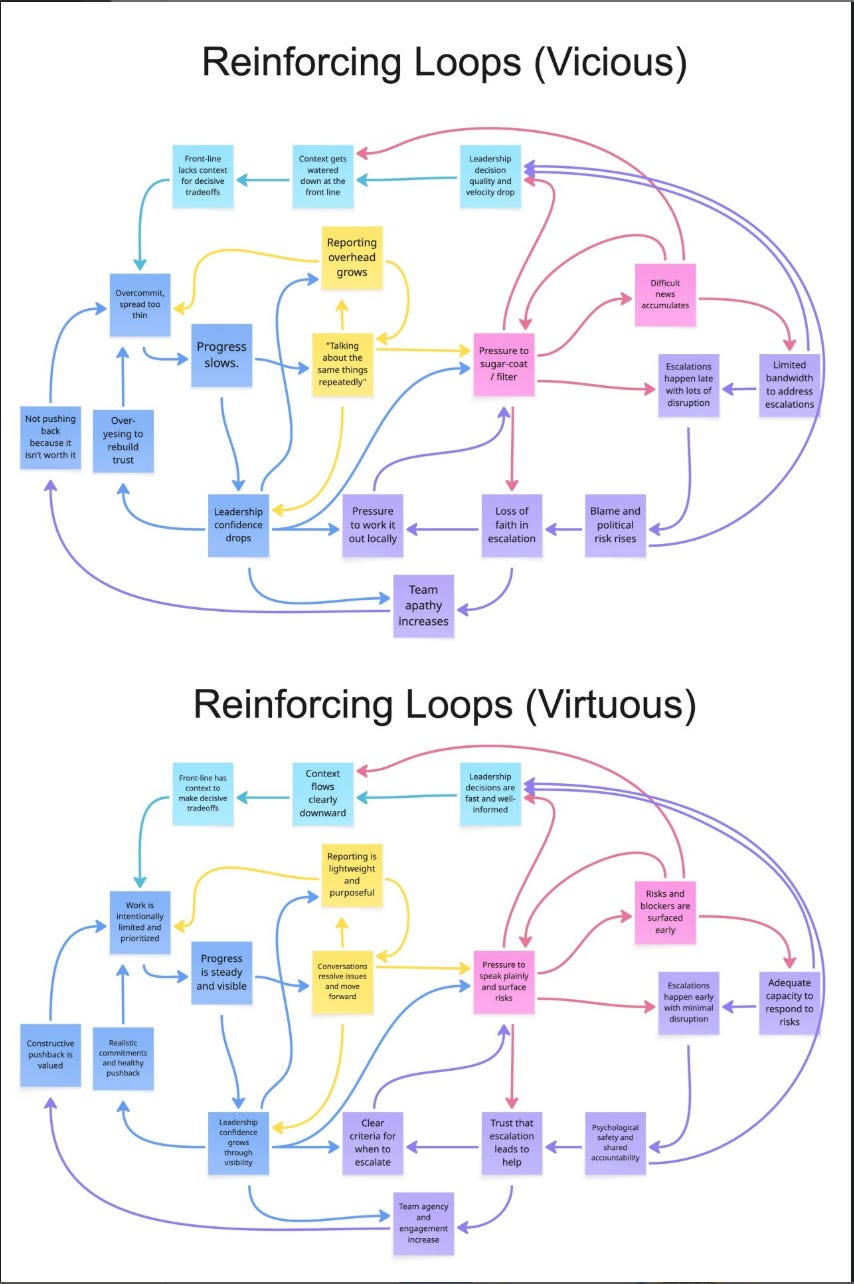

Escalation dynamics: Why learning from failure is difficult

When things go well, people avoid “jinxing it” and relax scrutiny. They stop trying to understand what’s working. When things go poorly, scrutiny increases and pressure builds to find a root cause.

The paradox is that as systems spin out of control, single causes are harder to find, and the push for scrutiny can start contributing to the problem.

Escalation dynamics are a great example of this...

If the default approach to failure is “find the root cause” (often meaning “find who to blame”), and the default approach to success is “if it’s not broken, do not fix it”, then you limit your ability to learn and operationalise only those approaches.

These evaluation models by John Cutler are a great example. The vicious loop (“Working harder loops”) often reinforce poor behaviour and reduce learning, because they drive more of the same under stress.

If the focus switched to a learning mindset (virtuous loop) in both success and failure, you are more likely to find the changes that improve the system of work.

But for that to work, you usually need people willing to work across discipline boundaries, psychological safety, showing fallibility and a supportive leadership, that embraces learning rather than punishing failure. Via When things go well, everyone takes credit. When things go poorly, everyone looks for someone to blame. | John Cutler | Linked

Past Linkys

Linky #24 - Principles, Practice and Reality

This week’s Linky is all about how teams define “good”, then build feedback loops to protect it. From Continuous Delivery principles, to quality strategy, to the messy reality of UI and human behaviour. Plus: I’m experimenting with an audio version of Linky, let me know if it’s useful.

Linky #23 - Change, Visibility, and Predictability

This week’s Linky is about what makes change stick in engineering teams. Not better slogans or new role names, but social proof, visible work, and the conditions that make releasing feel normal.

Linky #22 - Capability Beats Heroics

This week’s Linky has one theme running through it: capability beats heroics. Whether it’s automation, flow, team dynamics, or decision-making, the same lesson keeps showing up. If you want speed and quality, you build the foundations that make good outcomes repeatable.