This week’s Linky is all about how teams define “good”, then build feedback loops to protect it. From Continuous Delivery principles, to quality strategy, to the messy reality of UI and human behaviour. Plus: I’m experimenting with an audio version of Linky, let me know if it’s useful.

Latest post from the Quality Engineering Newsletter

I’m going to be diving deeper into failure over the next couple of posts, and I’m kicking off with something I’ve been meaning to write about for years.

Talking about and sharing failure is hard because we often see failures as “bad” and something to avoid. But they will happen, so how do we make it easier to learn from them?

One starting point is recognising that not all failures are equal, and that better classification can help. This scale shows that failures tend to sit on a spectrum, but when you apply it to software incidents, you quickly see it’s rarely “one thing”. It’s usually multiple factors interacting, and calling it a generic failure misses that nuance.

Dive into the post to see how you could apply the scale in your context.

🎧 New experiment: Audio linky

In the last issue of Linky, I tried a new format so people can consume Linky in a different way: podcast-style. It’s not a straight reading of the post. It’s more narrative-led, with me sharing a bit more of my thinking on the links.

You can still read the usual format below, but do check out the audio version and let me know what you think.

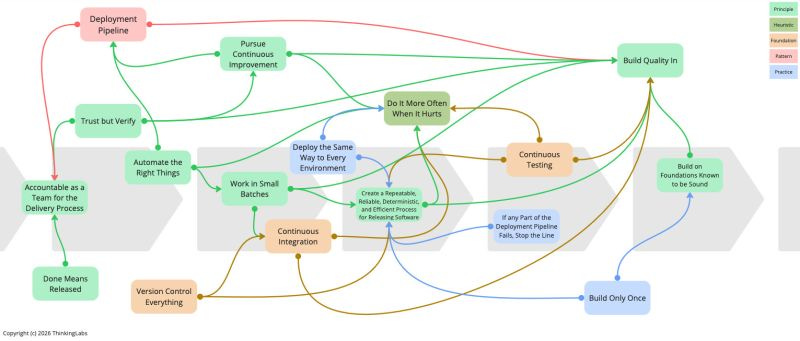

What does Continuous Delivery really mean?

There is a lot of misunderstanding about what Continuous Delivery actually is and what it entails.

It takes nine principles, one heuristic, three foundations, one pattern and three practices to practice truly Continuous Delivery

Great way to visualise Continuous Delivery. I particularly like how he calls out principles (green), practices (blue), and foundations (orange). With most of the model being principles.

The thing about reading other teams ways of working is you need to adapt them to your context. A principle like “automate the right things” will look different for different teams. But a practice like “deploy the same way to every environment” is more about consistency of approach, even if the exact implementation is shaped by each environment. Via What is Continuous Delivery? | Thierry de Pauw | LinkedIn

What makes someone a quality engineer?

Early agilists had such overwhelming success in helping teams to deliver more value that the demand for expert guides quickly outpaced supply.

This created another goldrush in training, combined with a lack of leadership, capability in identifying competent experts, and providing them required support, which led to an explosion in ‘coaches’ and ‘Scrum Masters’ whose entire professional foundation rested on a two-day introduction course to one agile framework, and a few years working in a highly dysfunctional organisation that would quickly overwhelm their ability to recognise and influence good practice.

When you spend most of your working life mired in bad practice, you cease being able to recognise what good looks like.

This made me think about the explosion of “quality engineers”.

There are many people who have been renamed from tester to QE, and only a handful who have hands-on experience of enabling teams to build quality in. Are a couple of training courses and a title change enough? And what does “successful QE” even look like?

What’s interesting is that many of the things Michael says Agile practitioners don’t fully grasp are also things I see many QEs struggle with. I’ve been guilty of shortcutting this as “agile knowledge”, but what’s called out here is useful for QE folks to understand, too: budgeting, WIP, resource management, forecasting, and emergence (I’ve written about this one a few times). Via How Agile Coaches Killed Agility - by Michael Lloyd

Good strategy, bad strategy

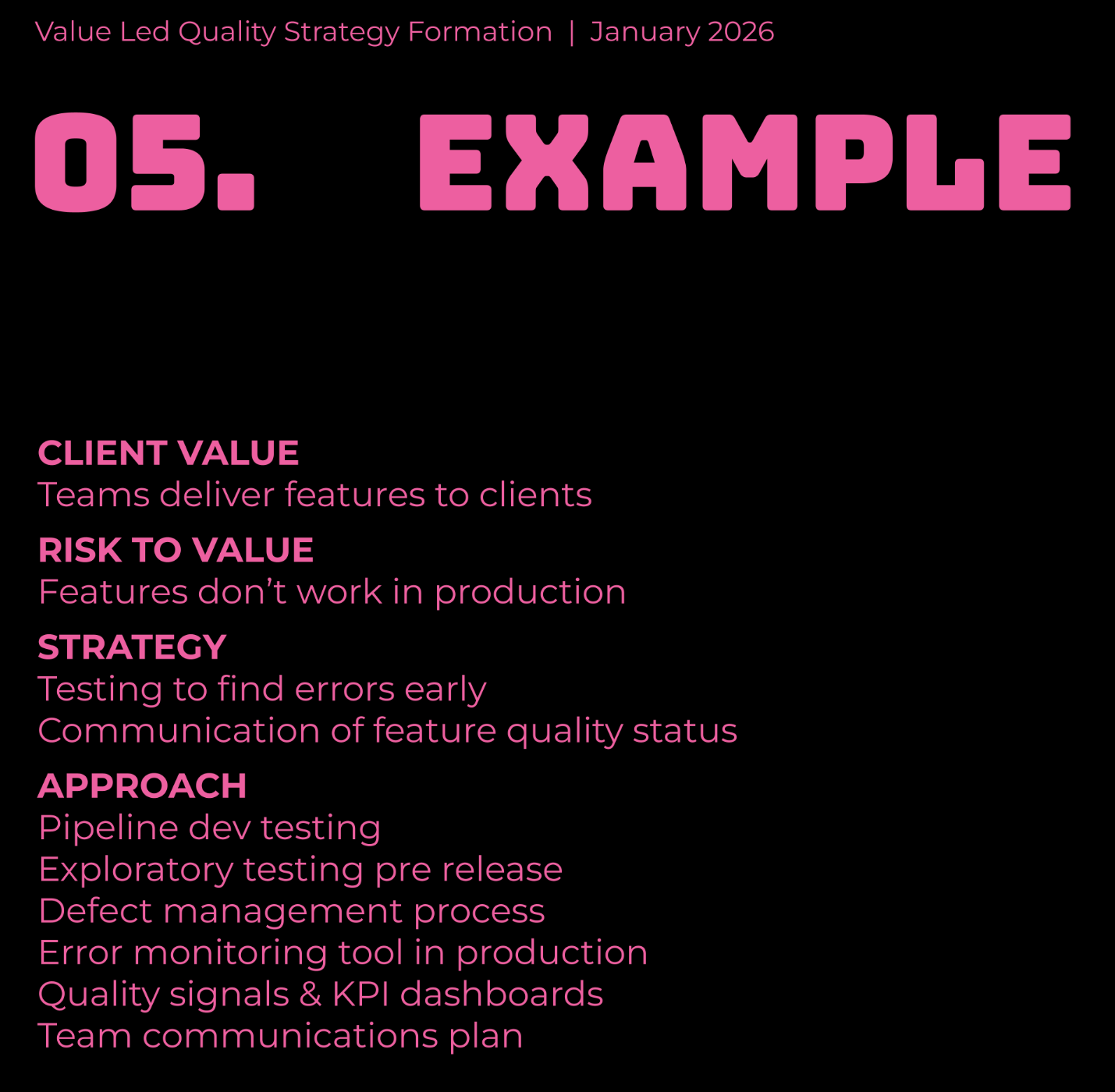

Value led formulation of a quality strategy

Goal: Client value - What do users want from a product?

Problem Diagnosis: Risk to value - What stops each value from being met?

Guiding policy: Principles and strategy - What will you do to mitigate and minimise the risk?

Coherent action: Approach & ways of working - The concrete actions teams will take to implement the policy.

Great infographic by Callum looking at how you can use the ideas from the book Good Strategy Bad Strategy to develop your quality strategy. He walks you through it step by step with an example, so well worth a look.

I like how it explicitly focuses on the problem statement your goal is trying to solve, and then moves through to concrete actions. It makes strategy more tangible than the usual “vision statements”, where people still need to figure out the how.

The way I see it, the goal maps to the quality attributes your stakeholders care about. Diagnosing the problem requires stakeholder input, as well as info from QEs on how quality is created, maintained, and lost in your system. Techniques like layers of testing and software feedback rings can feed into guiding policy, and a quality mapping session can help teams agree on coherent actions. Via Value Led Formation of Quality Strategy Infographic | Callum Akehurst-Ryan | LinkedIn

How would I respond?

The other week, I was listening to an older episode of The Vernon Richard Show (great show if you’re not subscribed), and I found myself doing something I’ve not really spoken about before.

As they were discussing topics, I noticed I was also thinking: how would I respond to that question or line of thinking?

It’s a habit I picked up after watching a panel discussion and thinking, “I’d never be able to do that.” So I started practising by thinking through how I’d answer. Over time, it helped me form opinions on many topics, and also get better at forming a view on topics I’d not even considered. It’s helped my communication skills, and also made panel discussions more enjoyable. Give it a go sometime. Via When Everything Sounds Like Testing | The Vernon Richard Show | Podcast

When UI meets UX: Struggles of resizing windows on macOS Tahoe

It turns out that my initial click in the window corner instinctively happens in an area where the window doesn’t respond to it. The window expects this click to happen in an area of 19 × 19 pixels, located near the window corner.

If the window had no rounded corners at all, 62% of that area would lie inside the window. But due to the huge corner radius in Tahoe, most of it – about 75% – now lies outside the window

I’m not sure how this came about, so I’m making a few assumptions. But to me, this is a great example of what can happen if you rely only on automated testing and telemetry to assess whether something “works”.

Automation, from code level to UI level, can tell you the behaviour works as coded. Telemetry can tell you how often it’s used and whether errors are thrown. But neither will reliably surface “this feels broken” when the UI technically functions.

Only real people using it are likely to pick this up, either by watching them use it, running usability sessions, or doing exploratory testing. Via The struggle of resizing windows on macOS Tahoe

Tests exist to support good design, fast feedback and safe change

Tests exist to support good design, fast feedback, and safe change. If they don’t do that, the label you give them is irrelevant. Software engineering improves when we stop defending rituals and start optimising for outcomes.

This got me thinking.

Automated tests can support good design, fast feedback, and safe change, but none of those terms are objective. “Good design” depends on how a team defines quality. “Safe change” depends on the kinds of risk they are trying to mitigate.

Automated test feedback also only tells us about known knowns. That means teams need to be explicit about what they are optimising for: what good looks like in their context, what kinds of change they want to protect against, and which tests best support those goals.

To cover known unknowns and unknown unknowns, teams need additional feedback mechanisms beyond automated tests, such as monitoring, production metrics, exploratory testing, and customer feedback.

So the principle is useful, but the devil is in the execution. What can look like “defending a ritual” is often a recognition that how tests are designed and used has a much bigger influence on outcomes. Via Tests exist to support good design, fast feedback, and safe change. | Dave Farley | LinkedIn

Closing thought

If you try the audio version of Linky, I’d love to know: was it actually useful, and what would you change to make it better?