Linky #23 - Change, Visibility, and Predictability

Build the conditions, then let quality emerge

This week’s Linky is about what makes change stick in engineering teams. Not better slogans or new role names, but social proof, visible work, and the conditions that make releasing feel normal.

Trying something new this week. If you’d prefer to listen instead of read, there’s a podcast-style version too.

Latest post from the Quality Engineering Newsletter

If you want a starting point for 2026 quality improvements:

Three practical “boosts” per challenge (technical, social, measurement), plus a tiny experiment (”nudge”) to get moving with your quality improvement strategies.

If you want more:

A mega Linky post with 100 insights themed into problem areas, each with an actionable next step. Give it a skim and see what catches your eye.

Our beliefs about change are often the biggest barrier to leading change

Deliberately starting where there’s already energy & enthusiasm & building out from a local majority (eg., three allies in a room of five) instead of trying to convert everyone first.

Intentionally working through & connecting peer networks so people are influencing “others like us”, rather than relying on one-to-many broadcasts

Creating early proof through local majorities that “people like us are already doing this,” tapping into social proof rather than abstract persuasion techniques.

Expecting that some people will resist change & take steps to work with it, rather than assuming that better messaging will win “resistors” over

Focusing less on increasing information and more on enabling people to see others like them succeeding with the new behaviours, so they can appropriate and adapt the change as their own.

We should leverage this approach when introducing quality engineering into organisations or any type of change. Try this: find three allies, run one small experiment and share the proof to build buy-in. Via Overcoming Barriers to Change | Helen Bevan | LinkedIn

Operational transparency to advocate for QE work

When we don’t speak up about our work, we create the following problems:

The Information Tax where your manager must “fish” for details to justify your team’s existence. That is energy they should be spending on strategy.

The Advocacy Gap: You aren’t giving your manager the “ammunition” they need to defend you or your budget in “the room.”

The Ownership Void: Without a narrative, you give the organisation permission to overlook you.

If you stay quiet, you aren’t just hurting your own career; you are failing your team. You make their work just as invisible as yours. You leave your advocate unarmed.

I don’t call it managing up anymore. I call it Operational Transparency!

This is why we need to advocate for the work we do and the teams we support. If we do not, someone else will fill the void, and we make our advocates work harder than they should have to. Make it easy for them to back you: give them a clear narrative and concrete examples. If that still does not translate into support, it tells you something important about the environment you’re in. Via Breaking Down Operational Barriers with Transparency | Manogna Machiraju | LinkedIn

Predictability is a characteristic of high-performing teams

Frequent releases are a signal that the system can absorb change without drama. They tell you batch size is small, feedback is fast, and integration happens early. Teams that struggle to release often aren’t slow. They’re fragile. Every release feels risky, so they batch work to feel safer. Ironically, that makes each release riskier.

Frequent releases as a signal is such a simple observation, but it’s often conflated with orgs simply wanting to go faster. Now, when you couple frequent release measures with stability matrices, it tells you if they can make small frequent releases that are stable. If they are, this team is highly likely to deliver predictable releases too. He goes on:

On the trail, predictability didn’t come from knowing every mile. It came from knowing how I moved, how the system behaved, and how much uncertainty I could absorb and still keep going.

Predictability isn’t something you can demand from teams. It’s something the system earns over time.

You don’t get it by tightening the schedule. You get it by removing the reasons work behaves unpredictably in the first place. And when you do, frequent releases stop feeling ambitious.

They just feel normal.

This is why quality engineering is all about learning how the system creates, maintains and loses quality. Because it’s with that insight that you can start looking for ways to build quality in and limit the things that cause the loss of it - stability!

Predictability is just like quality in that it emerges from how the system behaves, you can’t just add it on. Via Chasing Predictability | Alan Page

Bug fixes cause more bugs

[Due to]

- 𝐅𝐢𝐱𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐢𝐚𝐬 – focusing narrowly on the problem in front of you

- 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐢𝐚𝐬 – looking for evidence the fix works, not how it might fail

When we fix things, we can fixate on the immediate problem and only look for evidence that the fix works. Add delivery pressure, and we become less diligent, which is how fixes quietly introduce new problems. I remember plenty of early-career “bug fix ping pong” where the symptom moved, but the underlying learning never stuck.

What to do:

Review the incident and identify what you missed the first time, especially adjacent areas.

Add earlier detection: monitoring, alerting, and tests that would have caught it sooner.

Apply the fix, then deliberately check the nearby behaviours it could disturb.

Sometimes you’ve got to go slow to go fast. Via Fixing bugs causes bugs | Robert Meaney | LinkedIn

Are we approaching quality engineering in the wrong way?

Whenever a “model” gets popular, you see a rush to break it down into structures, roles and responsibilities, competencies, assessments, etc. These instincts make sense, because to “do” something, you need ways to assess whether you are “doing” it, and what doing it actually looks like.

But it also makes a critical error.

It assumes that the best way to get somewhere, is to behave and act like you’re already there. You substitute signals of a state (roles, behaviors, artifacts) for the conditions that actually produce that state (judgment, learning, constraint, responsibility). This is a form of means–ends inversion, where the artifacts of a (theoretically) mature system are treated as the path to maturity itself.

The rush to create quality engineers and get them to work a particular way gives organisations the impression they’re now doing quality engineering. But really, nothing meaningful has changed. They haven't done the learning to help them achieve the outcomes they want. No wonder so many transformations fail. The real work is the learning that needs to happen before the re-org. Via Product Operating Model Adoption May Be Misguided | John Cutler | LinkedIn

How do we better reward maintenance of software?

If we want more of it to happen, people need:

• intent (someone choosing to prioritise it)

• a way to surface what they’re learning from it (so the work feels visible and meaningful)

• social reward (so the effort is recognised, not taken for granted)We give through the work we do, and we keep going when that work gets noticed.

This came about as I was reading Tim Harford’s post on why self-improvement starts with maintenance, and it got me thinking about software maintenance. In engineering, we love the new and shiny. But we rarely stop to appreciate the people who keep things working.

Which reminded me of my 2025 New Year’s intent: go to more meet-ups. I didn’t set a target or know how many I’d manage, I just wanted to make more of an effort. I would’ve been happy with one a month, but I ended up averaging nearly two.

What kept me going changed over time. At first, it was simply turning up (intent). Then it became sharing what I learned, and sending kudos to speakers and organisers (surfacing learning). After about ten meet-ups, it turned into a bit of a personal challenge (how many can I fit in?). And by the end of the year, I was thinking more about my overall takeaways. And all the little likes and comments definitely gave me an ego boost 😆 (social rewards).

So if you want more maintenance, reward it deliberately, and make the learning visible. Via Rewarding Software Maintenance: Intent, Visibility, and Social Recognition | Jitesh Gosai | LinkedIn and you can read more about what I learned from 21 meet-ups via This year I set myself a goal: go to more meetups. | Jitesh Gosai | LinkedIn

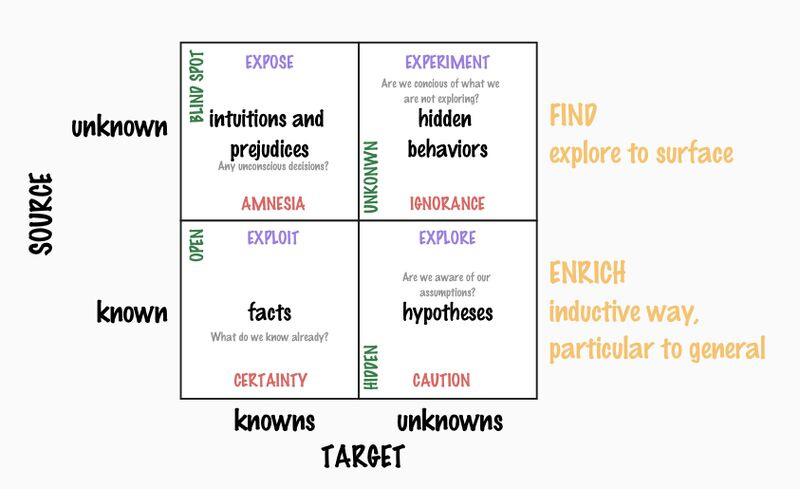

Exploratory testing isn’t about unknown unknowns?

Some people say exploratory testing is about the unknown unknowns. It is not. Even things that are known knowns to some, are not known to others, and exploratory testing is about balancing the information availability

Exploratory testing helps with both known-unknown and unknown-unknowns to uncover information about your software systems. Essentially, it reveals information asymmetry between people and systems. But it can also surface novel risks about the system before your users do. I should have made this distinction clear in my Testing Unknown Unknowns post. Via Some people say exploratory testing is about the unknown unknowns. It is not | Maaret Pyhäjärvi | LinkedIn

Katja Obring’s five QE priorities to cut through the noise

At some point last year I made a short list of what I want to focus on in my role as a QE. Not a definition, just priorities. It helped me cut through a lot of the confusion.

Katja’s QE priorities:

Quality is subjective and defined by stakeholders and users.

We can not engineer quality itself, but we can engineer the conditions that make valued outcomes more likely.

Quality Engineering focuses on improving feedback, decision-making and learning across delivery.

Testing is one input judgment, not a guarantee and not a gate.

Developers are responsible for testing. QA and Quality Engineers help shape quality, build frameworks, improve feedback loops, and better support decision-making.

To me, these read like grounding principles. They help you explain what you’re optimising for, especially when QE is still misunderstood. And they should evolve. As you learn about your context and your organisation learns what QE is, your priorities should change too. As Katja says in her post: “Quality work shows up in many forms, and pretending there is one right definition rarely helps.” Via Cutting Through QA vs QE Confusion with Intentional Focus | Katja Obring | LinkedIn