Scale of Failure

A practical way to talk about failure without blame, so we can learn faster and build quality in.

We tend to treat all failures the same. This pushes teams into one of two defaults: root cause analysis for everything, or a quick patch and move on. This scale helps you pick a response that improves the system, not just the symptom.

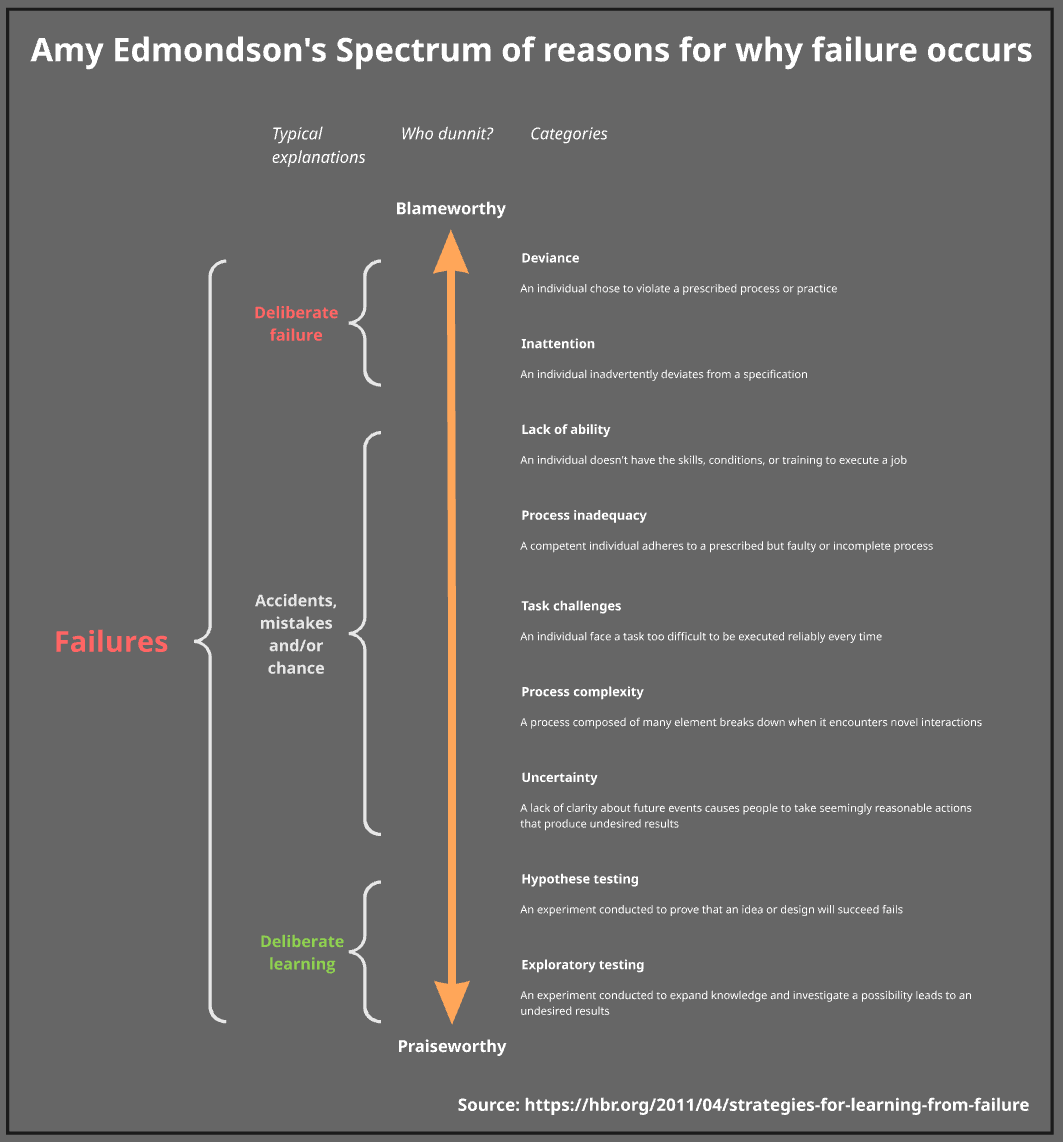

Spectrum of reasons for why failure occurs

How? Well, this is where we can borrow some ideas from Amy Edmondson’s 2011 HBR post Strategies for Learning from Failure. In this post, Amy shared a spectrum of reasons why failure occurs.

Her spectrum places failure on a range from praiseworthy to blameworthy. Praiseworthy failures are all about learning, while blameworthy failures often feel deliberate. Everything in between tends to be accidents, mistakes, or chance.

Note: Amy wasn’t saying we should literally blame people for failure. It was more about how people tend to feel about the reasons for failure in that range.

How does the scale help?

Let’s say an engineering team makes a release, and their error rates start to spike, so they roll back to investigate. During the investigation, it turns out the spike was caused by a misconfigured dependency. The failure wasn’t picked up by their tests because the error was only visible in the logs.

This incident contains a few different failure types, and each one points to a different improvement response:

System complexity: They didn’t expect the dependency to fail silently.

Slip: The dependency could be misconfigured, even with a clear plan.

Process inadequacy: Their testing layers didn’t include checks for errors in logs.

By classifying the failure types involved, we can see more clearly what to improve and avoid jumping straight to one default response.

Possible responses could be:

System complexity: increase observability, add contract testing where it fits, and reduce silent failure modes.

Slip: strengthen config validation, set safer defaults, and pair on risky changes.

Process inadequacy: add log-based assertions and alerts, introduce a small number of broad end-to-end checks that detect log error signals, and ensure production log alerting is in place.

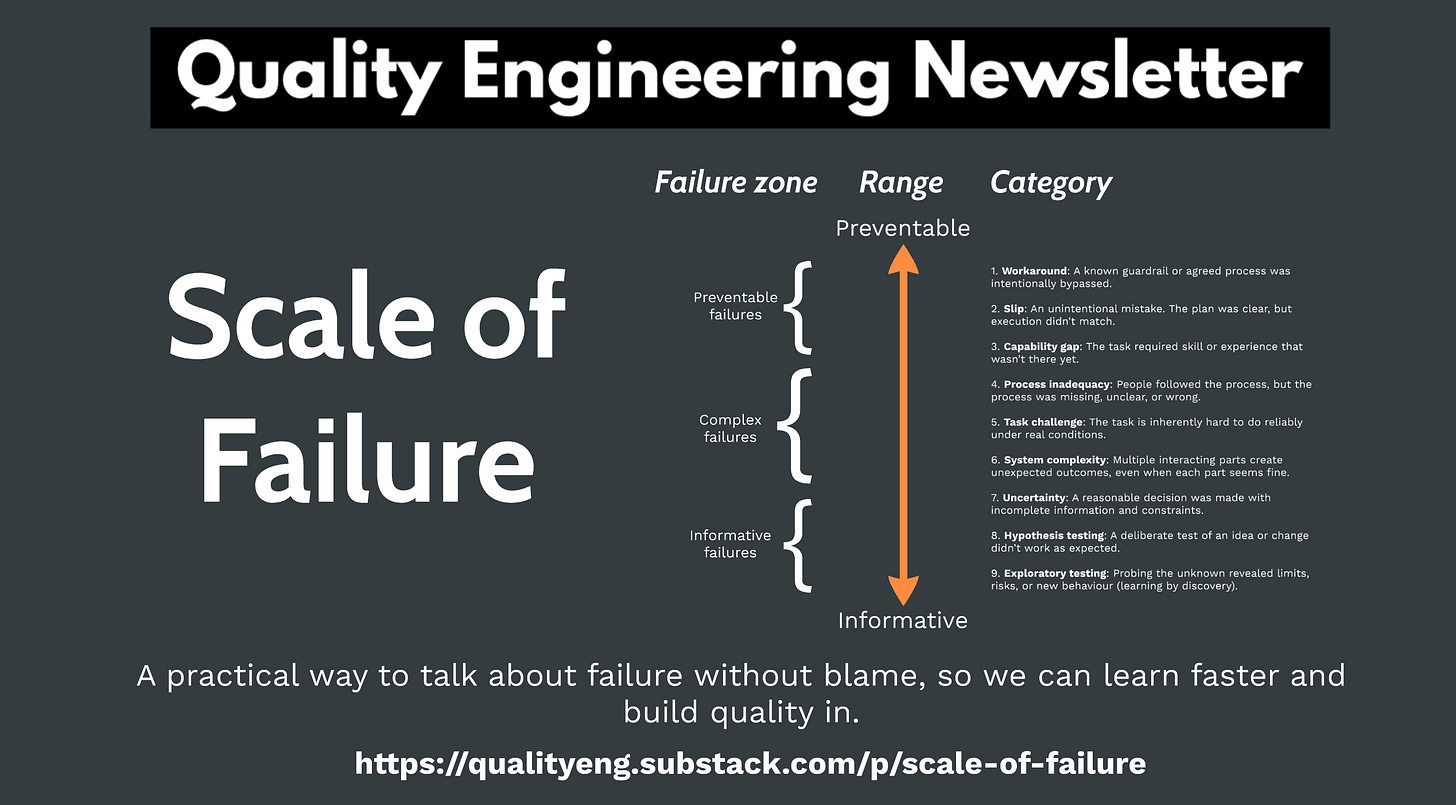

Updating the spectrum for engineering teams

With a bit of tweaking, we can use Amy’s spectrum and create what I call a scale of failure. This helps us have better conversations about what failure is and how we can learn from it.

I like the praiseworthy range of the spectrum, and it’s something we want more of in engineering teams. But the blameworthy range can work against learning from failure, so the first thing we need to do is shift the framing.

Some of the category wording can also feel accusatory, so changing that helps too.

From blameworthy and praiseworthy to preventable and informative failure

Instead of going from blameworthy to praiseworthy, I think it should be preventable to informative.

Failures towards the preventable range can often be improved through changes in the process or system of work. It becomes less about blame and more about: what could we have done differently?

Informative failures are still about learning and sit within the praiseworthy range. This is where failure is expected, and even encouraged, because it helps us learn.

From deviance, inattention, and lack of ability to workaround, slip, and capability gap

Deviance, inattention, and lack of ability can feel accusatory and won’t support learning, so we can make a few changes here.

The problem with “inattention” and “deviance” is that they can push us towards the idea that people intentionally violate a process to cause harm. But there are often environmental factors involved.

Maybe the instructions weren’t as clear as people thought. Maybe they were easy to misinterpret. Maybe someone believed they could achieve the same result in a more efficient way. Or maybe it was a high-pressure environment, and performance degraded in a very human way.

So let’s shift these to:

Deviance to Workaround: a known guardrail or agreed process was intentionally bypassed.

Inattention to Slip: an unintentional mistake. The plan was clear, but execution didn’t match.

“Lack of ability” is also too focused on the person and can easily feel like blame, so let’s reword it to:

Lack of ability to Capability gap: we lack the skills or experience to do the task (yet).

Scale of failure

The scale of failure is inspired by Amy Edmondson’s spectrum of reasons for failure, ranging from preventable to informative.

Most incidents contain more than one failure category. The aim isn’t to find the one true label, it’s to find the right learning response.

1-3: prevent repeats. 4-7: handle surprises. 8-9: learn on purpose.

Workaround: a known guardrail or agreed process was intentionally bypassed.

Slip: an unintentional mistake. The plan was clear, but execution didn’t match.

Capability gap: the task required skill or experience that wasn’t there yet.

Process inadequacy: people followed the process, but the process was missing, unclear, or wrong.

Task challenge: the task is inherently hard to do reliably under real conditions.

System complexity: multiple interacting parts create unexpected outcomes, even when each part seems fine.

Uncertainty: a reasonable decision was made with incomplete information and constraints.

Hypothesis testing: a deliberate test of an idea or change didn’t work as expected.

Exploratory testing: probing the unknown revealed limits, risks, or new behaviour (learning by discovery).

Once you start classifying failures like this, you’ll notice a lot of issues in software systems sit around process inadequacy, task challenge, system complexity, and uncertainty. These are complex failures. They’re hard to predict because external factors only become visible as we do the work. So the goal shifts to detecting, absorbing, and recovering quickly, through better observability, smaller changes, safer releases, and less coupling.

Classifying potentially preventable failures as workarounds or slips is also more psychologically safe to discuss. These labels reduce the risk of judgement and embarrassment, and make it easier to talk about what in the system led to the bypass or the mistake.

Capability gap leans away from personal blame too. It focuses on what support, learning, or experience is missing, rather than who is “at fault”. With workarounds, slips, and capability gaps, we want to make the right approach the easy approach: better guardrails, understandable defaults, training, and tooling.

None of this removes the discomfort of failure entirely. It still needs leadership support and intentional psychological safety. But it gives teams a better starting point.

The last two types of failure (hypothesis testing and exploratory testing) are informative failures. These are the “we chose to learn” failures: running experiments safely and capturing the learning. Techniques like feature flags, small blast radius, and clear success and stop signals make those experiments safer.

Most importantly, this scale helps us classify failures, not people. That makes it easier for teams to share what happened and learn from it.

How to use the scale

We now have a scale of failure, but how could we use it?

One area is introducing it as a shared language. That means being specific about what happened, running a short workshop to help the team get a feel for the terms, and agreeing on when to use them. You could even add them to your team charter.

Then, encourage the language in operational incidents and post-incident reviews.

Here are some ways to get started.

Step 1: Placing failure on the scale (together)

Use a real incident from your team, or something from the news, and ask:

“Where does this sit, roughly, and what makes you say that?”

Prompts that are hard to argue with:

Was there a known expectation or guardrail? (points to 1–4)

Did the system behave unexpectedly when things combined? (points to 5–6)

Were we making the best call with uncertainty? (points to 7)

Was this an intentional learning outcome? (points to 8–9)

Step 2: Match the learning response to the type

This is the bit most teams miss. They use root cause analysis for everything (and there is no single root cause for complex failures).

If it’s 1–3 (Preventable):

Improve clarity, training, tooling, or constraints

Strengthen guardrails (automation, checks, defaults)

Make the right path the easiest path.

If it’s 4–7 (Complexity-related):

Increase observability and feedback loops

Reduce coupling, add circuit-breakers, and improve rollback paths

Rehearse scenarios, improve detection, tighten release signals (testing, metrics, etc)

Focus on system conditions, not who missed it.

If it’s 8–9 (Informative):

Capture the learning explicitly (what did we rule in or out?)

Turn it into a repeatable experiment pattern

Add safety rails: smaller blast radius, feature flags, staging, monitoring

Step 3: Close with a learning habit

Finish with questions that reinforce learning:

What did we learn about the system?

What did we learn about our approach?

What will we change next time: guardrails, signals, or experiments?

A small but important tweak for psychological safety

Even with softer labels, people can still feel they messed up. When introducing the scale, make an explicit rule: We classify failures, not people.

The aim is to learn and find the right improvement response, not to assign character judgments.

Close

So the next time something goes wrong, instead of just calling it a failure, look to learn what happened. Try classifying it into one of these categories to help others understand what happened and how to learn from it.

Rather than what typically happens with failure, with people trying to ignore, deny, divert or worse, blame.

This is brilliant stuff. The way you reframe system complexity failures to focus on reducing coupling instead of blaming individuals really resonates with me. I've seen teams spend hours in post-mortems trying to find the one person who 'caused' an incident, when the real issue was tight coupling betwen services that made failures cascade. Your preventable-to-informative scale gives teams a much more constructive lens for these conversations, dunno why more orgs dont adopt this approach.