Uncertainty of change

Embracing uncertainty in software development: explore why we react to change, how testing reduces complexity, and how curiosity helps teams build resilient, adaptable systems

Uncertainty and change are inevitable in our complex world, but our responses to them often vary—some ignore them, others deny them, and some try to resist them entirely. In this post, I'll explore why we react to uncertainty the way we do, drawing on real-world case studies and the psychology of uncertainty to help explain these responses.

I'll examine how software development is inherently uncertain and how some testing approaches can worsen this. By reframing how we think about testing, I'll show how to use it to reduce uncertainty and help teams navigate complexity more effectively.

To do this, we need to embrace curiosity and see change not as a threat but as an opportunity to learn and grow. By working with uncertainty instead of against it, we can build resilient, adaptable software that meets our users' evolving needs.

Key Takeaways

Practical strategies for embracing uncertainty and change.

Understanding complexity and its link to uncertainty.

How collaborative, lifecycle-spanning testing reduces uncertainty.

Please note that this is a long post with quite a few images, so it is best viewed in a browser/substack app rather than your email client, which is likely to truncate the post.

Change is everywhere

In 1779, a young textile apprentice working in Manchester called Ned Ludd feared the loss of his job and future due to the introduction of new machinery that looked to replace him and his fellow textile workers. So he took matters into his own hands and destroyed the machines. Other textile workers followed in his footsteps, saying they were taking orders from General Ludd. This was the first of the Luddite riots across England.

In the 1980s, Sears was one of the largest department stores in the world, mainly operating in the US; they were based in Chicago in the Sears Tower, which, when it opened, was the world's tallest skyscraper. However, during the 2000s, they were receiving significant pressure from other low-cost retailers and losing a lot of customers to them. So, instead of attacking those companies head-on, they decided to move into a fairly new market called online shopping. Interestingly, they pioneered many of the online models we now take for granted, such as free customer shipping and online marketplaces for other companies to sell through and click and collect.

In around 2000, Blockbuster was a $4,8 billion movie rental business, available in 1000s of locations and not to mention a lot of money in the bank, too. When one day, a CEO from a small, heavily in debt online-only DVD mail order company made them an offer. If Blockbuster bought their company for $50 million, they would run the online part of Blockbuster for them. The CEO who made them the offer was Reed Hastings; his company was called Netflix. Blockbuster, seeing little to gain from the deal and holding back their laughter at such bravado from the tiny company, declined the offer and chose to continue as they were.

Around 2010, Nokia was the king of the mobile phone business, but after facing stiff competition from Apple and Google, it released its range of iPhone killers. Unfortunately, they weren't up for killing much, and by 2013, Apple was king of the smartphone business, with Google not far behind. Seeing impending doom and unwilling to use Android for its operating system, Nokia turned to Microsoft. Who was also seeing the shift to mobile and playing catch-up with Apple and Google. So Nokia sold themselves to Microsoft for €7 billion and attempted to marry Nokia hardware know-how with Microsoft's mobile OS, hoping to claw their way back into relevance in the new smartphone era that was happening without either of them.

So, what caused Nokia, a company that had existed since the 19th century, to essentially sell itself to a competitor? Why did Blockbuster not see the vast changes coming from the Internet? Why did Sears try to shift to online when its core was always brick-and-mortar department stores? And what made the Luddites of 18th century England smash up their looms?

Well, before we get into that, first, a little about me.

Who am I?

My name is Jitesh Gosai, and I work as a Principal tester. Now, I don’t work in specific teams; instead, I collaborate across various organisational departments. My primary goal is to promote a culture of quality. This is one where, instead of inspecting for quality at the end of the development process like more traditional testing approaches, we look to build quality at every stage of development. From the products we build to the processes we use to build those products and into the very interactions of the people who use the processes to build our products. I call this approach Quality Engineering, and I help organisations build quality in by spending time with teams and seeing what is and isn't working. Then, work with them to see how we can improve their capability to do the work with an aim to do things better, faster, cheaper, but most importantly, sustainably for those teams.

Change leads to uncertainty

One thing I see pretty often in software organisations is change. It's everywhere, from the little things like whether you are coming into the office or working from home that day to our approaches to getting things done as a team. And luckily, a lot less frequently, what department you will be working in and who your line manager is. And you tend to find that those small organisational changes don't cause many problems, and things pretty much carry on as usual. But sometimes, they can be quite big and cause all sorts of disruption.

Those smaller changes are easier for us to handle because we can better predict what will happen and how it will (or not) affect us. Therefore, you can say there are high levels of certainty. However, those bigger changes can cause lots of disruption and all sorts of problems because we can't easily predict what will happen or how it will affect us. Therefore, you could say that there are high levels of uncertainty. And the kinds of problems those uncertain changes can cause can be things like:

People go along with it, hoping that things will return to normal once it's over.

People doing nothing and hoping that things will blow over.

People leave the organisation because of the change.

And people protesting and pushing back against the change, hoping they can stop it from happening.

These behaviours have one thing in common: they are trying to get us back to certainty. Because we tend to find that uncertainty is quite an uncomfortable sensation, so we try to get ourselves back to something that is more comfortable. But what makes uncertainty so uncomfortable?

How uncertainty affects the brain

The stress response

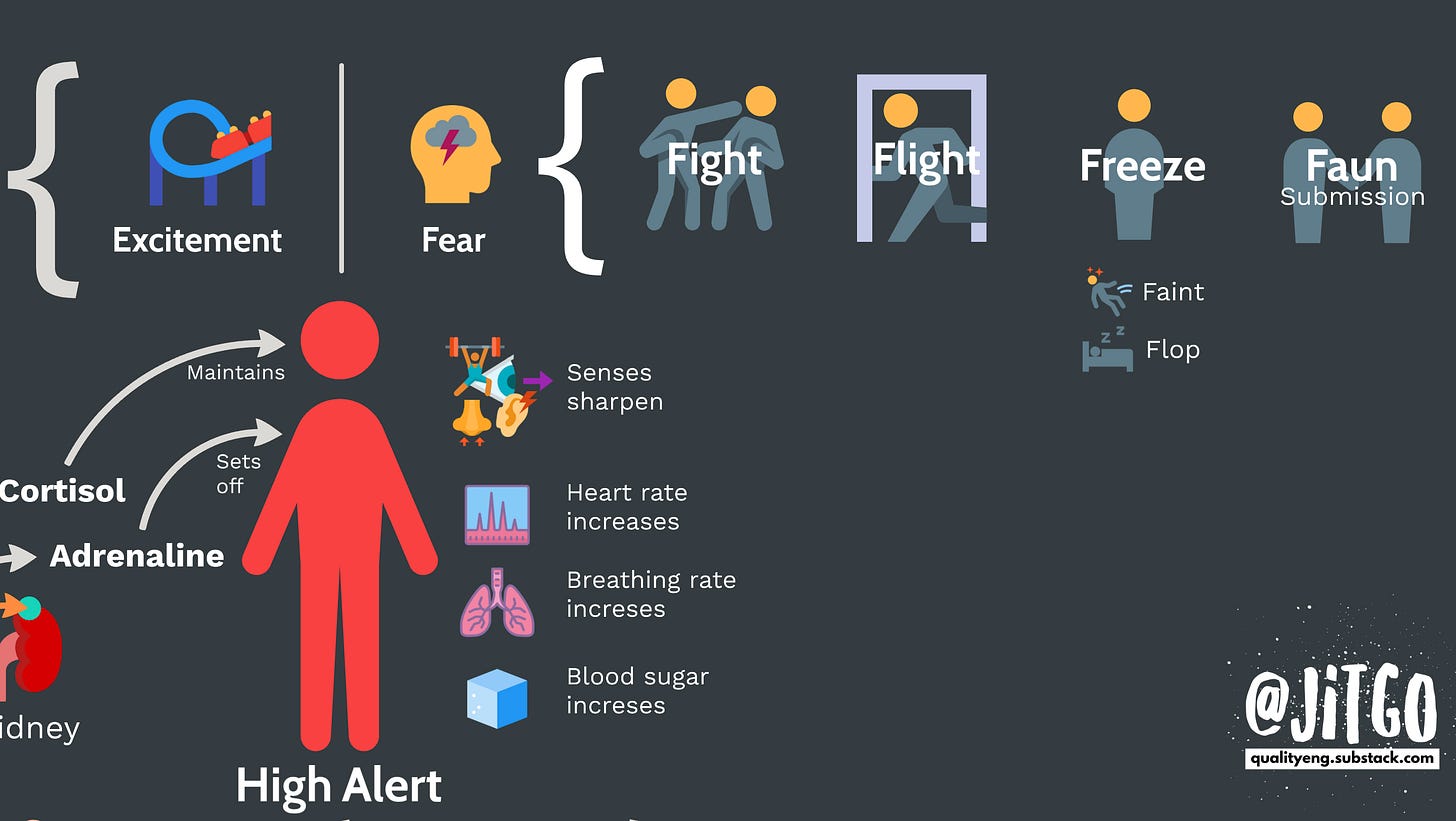

Well, your brain does some interesting things when it detects uncertainty. Our senses constantly take in information from our environment. This information passes through a part of your brain known as the amygdala. But when the amygdala detects stressors in the environment, it sends a signal to the hypothalamus, which tells the adrenal gland that sits on top of your kidneys to flood your body with adrenaline. And the fantastic thing about this is that all this happens even before the brain's visual centres have had time to process the stressor.

This automatic process is why you jump when watching scary movies. Even though we know the killer is about to jump out at the victim, we jump, as it's an involuntary reaction. This is your amygdala at work trying to protect you.

High alert status

When adrenaline starts circulating through your body, it puts you on high alert, which causes a number of changes. For example, your sight, hearing, and other senses become sharper, your heart rate increases, your breathing becomes more rapid, and your blood sugar levels increase. If the brain continues to perceive danger, then the hypothalamus signals the adrenal glands to release cortisol, keeping the body on high alert.

Once we're on high alert, our brain detects this alteration in the body's internal state. That’s when we actually experience the feeling of adrenaline, which can allow us to shape our behaviour.

Then, depending on the individual and the situation, we may interpret the high alert status in one of two ways: either as excitement or fear. For which there is a very thin line between these two states. Often, the critical difference is the story we tell ourselves about the changes in our environments.

The fear response

If we conclude that environmental stressors are bad, they can lead to a fear response. Then, depending on the severity of that stressor or the length of time it exists in the environment, we can often react in one of four ways. The two most commonly known responses are:

The fight response can include physical and verbal attacks. This is all about trying to restore us to a state of certainty.

The flight response is to psychically distance yourself from the situation and move towards something more certain.

The two other responses are

The freeze response and waiting for the stressor in the environment to go away. You see animals do this quite often when they are attacked. This can develop further into a fainting response where people lose consciousness. For instance, think of how people may react to the sight of blood or a needle of a syringe. It can also develop into the flop response, which is remaining conscious but losing control of your limbs. The freeze, faint, and flop responses are about seeing if the stressor goes away and back to certainty.

The final response is faun or submission, which involves making friends with the stressor to divert attention away from you, make you less of a threat to the stressor, and hopefully return to certainty.

These responses to uncertainty are not bad, especially if the stressor in the environment is a bear. They have evolved over millions of years and are there to protect us.

However, the interesting thing is that our brains can't tell the difference between a bear and a change in your team's ways of working. Our brains can detect any environmental change as a stressor and try to protect you by invoking your high alert status. And it’s all these bodily changes that can make uncertainty an uncomfortable sensation.

But not every situation results in a fear response

Not every uncertain situation will lead to a fully blown fight, flight, freeze or faun response. As individuals, we often respond in much milder forms to that discomfort. And when working in groups it can look a little different too.

So what happened to these organisations, and what’s uncertainty got to do with building high-quality software systems?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Quality Engineering Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.