Linky #18 - Seeing the System

Lessons from outages, metrics, and team dynamics on building environments where quality can thrive.

This week’s Linky is all about systems. Whether it’s how a tiny bug caused a global outage, why metrics can mislead us, or how teams can better support neurodiverse colleagues. Every post is about the environments we create and how they shape the quality outcomes we care about.

Latest post from the Quality Engineering Newsletter

This week’s post is a deep dive into the CrowdStrike outage of 2024. What I find is that most engineers know the technical cause: an array-out-of-bounds error. But the real lessons lie in the systemic factors that turned a small defect into a global outage. This post dives into:

How testing and review practices broke down in a high-trust, high-speed environment

Why traditional root cause analysis misses key organisational contributors

What this means for how we approach risk, quality, and change in complex systems

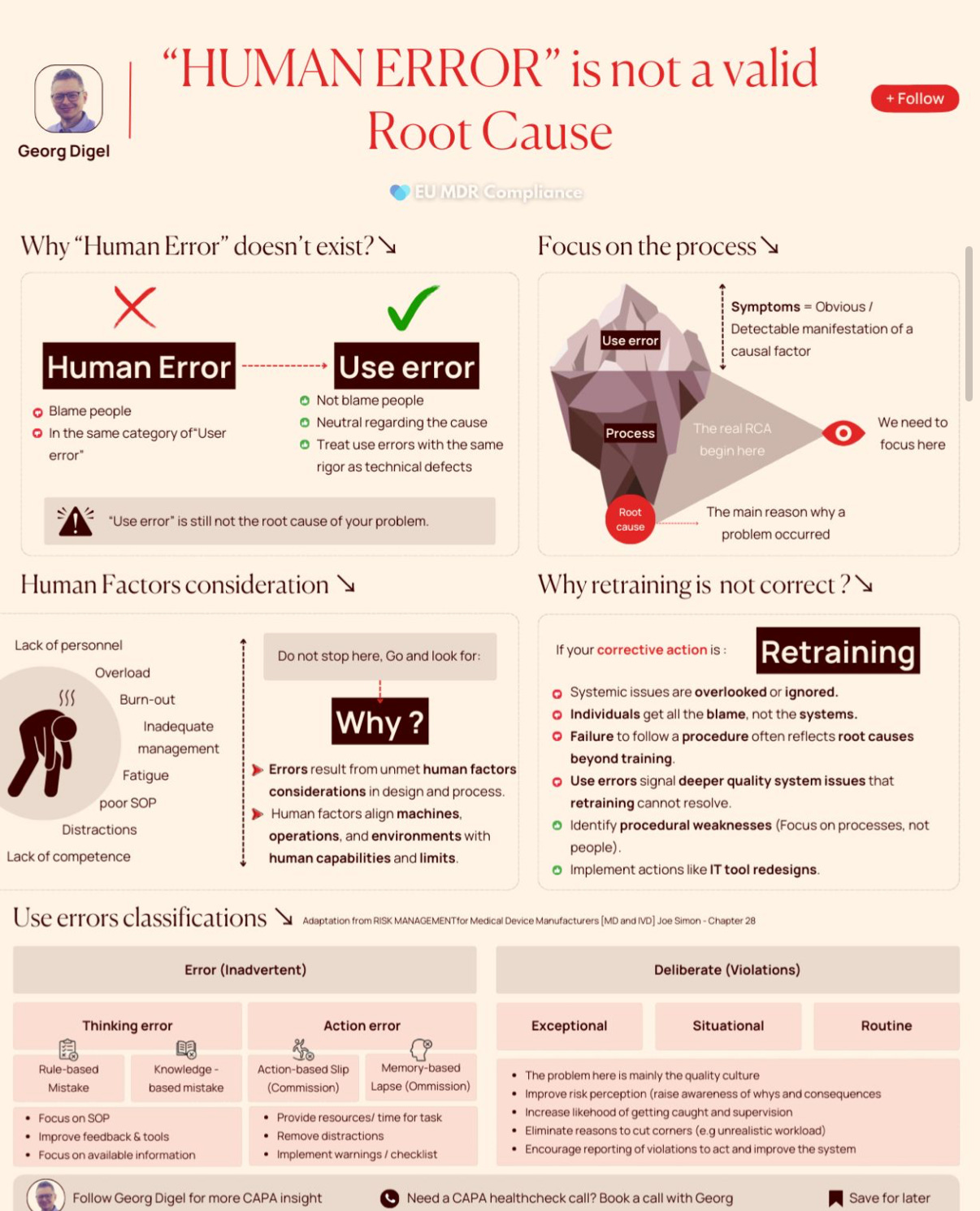

Use error, not human error

Human error” puts blame on individuals. “Use error” focuses on the context:

→ Was the procedure usable?

→ Were resources available?

→ Did the system align with human limits?

“Use error” is an interesting one. I’m not sure how well it translates to software environments (I feel most people would think of end users), but the point still stands. If you’ve arrived at human error for a production incident, you’ve probably only gone halfway to understanding the system problem. Treat it as a signal to dig further. Via “Human error” is never the real root cause. | LinkedIn

We need to talk about metrics

To borrow from Dan Sullivan, it’s less “how do I fix this?” and more “who or what can make this better?”.³

We need to create an environment where the most likely outcome is the thing you want. If we over-focus on testing activity, we lose sight of the outcomes that matter. So maybe it’s time to look at what signals can tell us how the system is working, before the results arrive?

This is what I mean when I talk about making the system we work in healthier, more conducive to the quality outcomes we want, and less of the ones we don’t.

Vernon goes on:

That means my next job is to connect the dots between the system I manage, the signals it gives off, and the goals the business actually cares about.

And that’s what a quality engineer does: enables their team to build quality in.

Great post by Vernon. Now, I’m biased as I consider Vernon a friend, but even putting that aside, this is a brilliant post on metrics and well worth a read. Via Rethinking Metrics - by Vernon - Yeah But Does It Work?

A better way to measure software teams?

Software work is highly variable by default

The strongest evidence for the features that improve software velocity are human-centered practices like coding time and access to collaboration.

Put your investment into environmental factors that encourage learning and growth, not trying to identify magical superprogrammers

Organizations vary tremendously from each other.

Be skeptical of comparisons between organizations that don’t account for this

An individual developer’s average cycle time is not a particularly good predictor for their future average cycle time.

Change in software metrics data is likely driven by a lot of factors that aren’t being measured in the current metrics. Managers who freak out and blame individual developers for some moment of lag are wrong, and software metrics are bad predictors without more context.

We conclude that improving software delivery velocity requires systems-level thinking rather than individual-focused interventions. Now a peer-reviewed scientific study published in Empirical Software Engineering (link in comments).

It always comes down to the system in which the work occurs. If you want to improve any quality attribute, that’s where to focus your efforts. Via Challenging software metrics with empirical evidence | Cat Hicks | LinkedIn

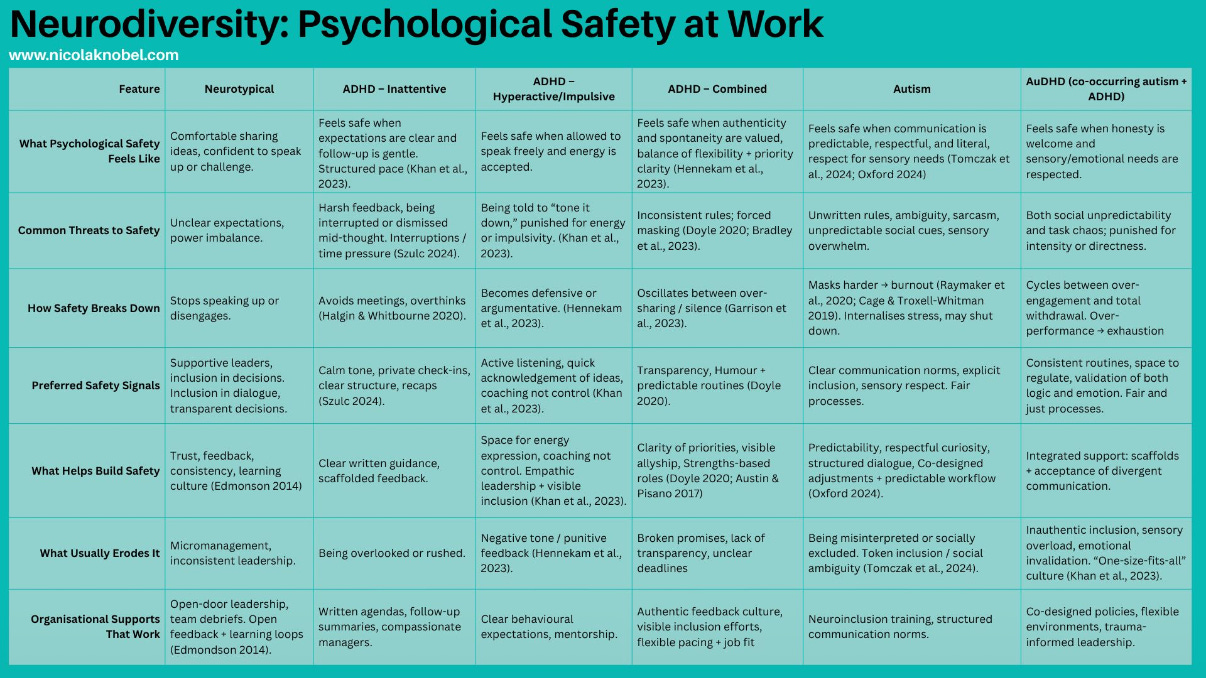

Psych safety and neurodivergence

Some excellent research has gone into this table. Psychological safety is one of the key environmental behaviours we need in engineering teams, but much of the advice out there is aimed at neurotypical people. This table helps you see what supports neurodiverse individuals. While each person is different, it’s a great starting point for designing environments high in psychological safety. Via 45% of you asked for a table for Psychological Safety in Neuroincusivity | Nicola Knobel | LinkedIn

It’s not about being an AI expert but about figuring out how to use them

pick a system and start with something that actually matters to you, like a report you need to write, a problem you’re trying to solve, or a project you have been putting off. Then try something ridiculous just to see what happens. The goal isn’t to become an AI expert. It’s to build intuition about what these systems can and can’t do, because that intuition is what will matter as these tools keep evolving.

The future of AI isn’t just about better models. It’s about people figuring out what to do with them.

This is good advice from Ethan, a professor of entrepreneurship, innovation and AI. The models are improving all the time, so whatever worked a year ago is probably outdated now. The table in the post is well worth a look to see the current state of the art. Via An Opinionated Guide to Using AI Right Now

Quality Engineering Newsletter Chats: Early thoughts on AWS Outage

Following last week’s CrowdStrike analysis, I’ve been watching discussions about the AWS outage with interest. One of the Reddit threads I follow had some interesting (unconfirmed) observations:

US-East-1 is the original AWS region, built before multi-region support existed

It still runs older hardware and services that even AWS doesn’t fully understand how to reconfigure

Because it must stay online all the time, it’s hard to test properly – issues often show up only when it goes down

It’s the default region for new apps, and most people just stick with that default

Building multi-region redundancy is expensive and complex

Testing failover means literally taking a region down, which is risky and hard to do safely

Most companies don’t run full disaster recovery tests because of the risk it might not come back

Many teams accept that US-East-1 outages are rare and just take the risk

Some companies have found recovery takes so long that by the time they’re ready, US-East-1 is already back

Managed services often depend on US-East-1, so even other regions can be affected when it’s down

For multi-region resilience to work, everything must exist in the backup region

miss one dependency and the whole setup fails

And as Daniel Billing mentioned in the thread, it’s the complexity of modern software.

I’d love to hear what you think about this one. Do these kinds of systemic risks come up in your own work? How do you approach testing for the unknowns?

Share your take (or just lurk and read along) in the Quality Engineering Newsletter chat.

Why can’t we just move on from the past

when we refuse to look at how we got here, we’re not being pragmatic. We’re just choosing to let the past shape the future unconsciously instead of deliberately.

This is why studying past incidents matters. It helps us understand how we got here, so we don’t unconsciously repeat the same mistakes. Via Why We Can’t Just “Move On” from the Past | Navarun B. | LinkedIn

Past Linky posts

Linky #17 - Learning by Doing

It’s conference season again, which means plenty of ideas, experiments, and conversations about how we build quality into our systems. This week’s picks explore how we learn best from hands-on experience, solid fundamentals, and small experiments. Whether we’re testing software, building resilience, or just trying to make sense of AI’s impact on our work.

Linky #16 - Knowledge, Courage, and Uncertainty

This week’s Linky brings together ideas about how we learn, adapt, and grow when we don’t have all the answers. From Buddhist parables to neuroscience, from quality engineering to public speaking, each piece explores a different angle on uncertainty. The common thread? Whether it’s knowledge, confidence, or resilience, it’s not about avoiding difficulty but about how we respond to it.

Linky #15 - Beyond Root Causes and Simple Fixes

This week’s Linky is all about working in complexity and the value of human judgment. From principles for using LLMs, to why root cause analysis often fails, to safety in discomfort. These are all reminders that quality isn’t about certainty or control, but about navigating risk, coordination, and the unknowns together.

Excellent curation on systemic thinking. The parallel between your CrowdStrike analysis and the AWS US-East-1 discussion is striking - both highlight how legacy systems with high uptime requirements become untestable in practice. The US-East-1 observation that 'it's hard to test properly – issues often show up only when it goes down' mirrors the high-trust, high-speed environment you described at CrowdStrike. The Vernon piece on metrics resonates strongly. 'If you've arrived at human error for a production incident, you've probably only gone halfway' is exactly right. The use error vs human error distinction is powerful, though I agree it's not as intuitive in software contexts. I'd argue it applies broadly: when a developer ships a bug, was the testig environment adequate? Were code review practices contextual? Did the deployment system align with the cognitive load? The Cat Hicks research on software metrics is game-changing - 'improving software delivery velocity requires systems-level thinking rather than individual-focused interventions' should be posted in every engineering manager's office. The neurodivergent psychological safety table is fantastic. These adaptations (clear expectations, written communication preferences, flexible time structures) actually benefit everyone, not just neurodiverse individuals. It's a great example of how designing for the margins improves the entire system.